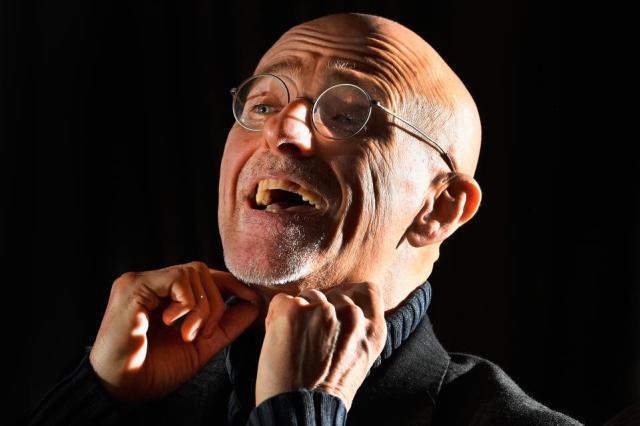

Head Transplants: Sergio Canavero Is About to Perform the First Human Surgery—and There’s Nothing to Stop Him

Sergio Canavero claims he can make you immortal, but there’s a small catch. He first wants to chop off your head.

If that’s not a deal-breaker, you’ll be happy to hear that the Italian neurosurgeon has announced he will perform the world’s first human head transplant in China sometime in December. (He’s vague on details, possibly for security reasons.) He will remove the head of a patient—an unidentified Chinese national—and attach it to a donor body, origin (and cause of death) unknown. The spinal cord will be fused and the blood vessels and muscles attached. The patient—same head, new body—will be kept in a coma for around a month while he (or she?) heals. Canavero says that if successful, his patient will eventually be able to walk again. If his plan sounds ludicrous, that’s because it is. Nobody knows how to fix a broken human spinal cord, and the scientific evidence that supports Canavero’s approach is highly questionable. Oh, and the ethics of performing an unproven procedure that jeopardizes one (or possibly two) human lives are sketchy, at best.

If that’s not a deal-breaker, you’ll be happy to hear that the Italian neurosurgeon has announced he will perform the world’s first human head transplant in China sometime in December. (He’s vague on details, possibly for security reasons.) He will remove the head of a patient—an unidentified Chinese national—and attach it to a donor body, origin (and cause of death) unknown. The spinal cord will be fused and the blood vessels and muscles attached. The patient—same head, new body—will be kept in a coma for around a month while he (or she?) heals. Canavero says that if successful, his patient will eventually be able to walk again. If his plan sounds ludicrous, that’s because it is. Nobody knows how to fix a broken human spinal cord, and the scientific evidence that supports Canavero’s approach is highly questionable. Oh, and the ethics of performing an unproven procedure that jeopardizes one (or possibly two) human lives are sketchy, at best.

None of that deters Canavero, so hold on to your hats.

Paging Dr. Frankenstein

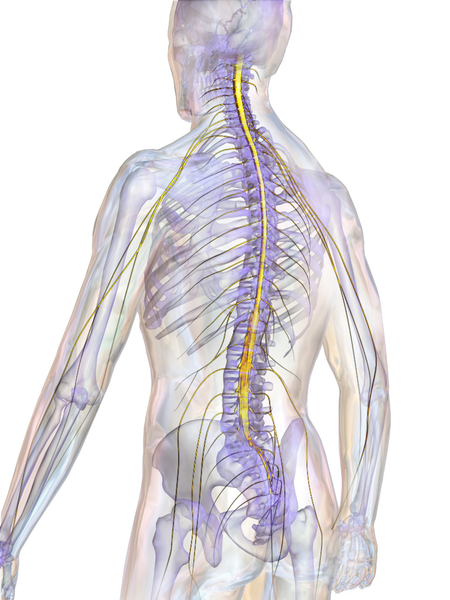

The human spinal cord is a long, thin tube of nerves that connects almost every part of the body to the brain. It is the pathway that allows the brain to give commands to the body, and the cells there are highly specialized—so much so that once damaged, they are effectively lost for good. Regenerating damaged spinal cord cells is extraordinarily difficult.

In the U.S., there are an estimated 12,500 spinal cord injuries every year, which is why Canavero is not the only scientist desperately trying to mend spinal cords. In the 1960s, renowned scientist L.W. Freeman experimented on rats, cats and dogs to find out if there were any circumstances under which spinal cords would repair themselves naturally. He removed small sections of spinal cords, then waited to see what would happen. Of the 66 animals that survived his surgery, six eventually regained what he deemed a “good” level of motor function.

That appeared to be an impressive achievement, but it did not necessarily apply to humans. The cut Freeman made was sharp and clean, but when humans injure their spinal cords, the tear is messy. Regardless, Canavero says Freeman’s work “shone light on the path,” inspiring him to delve deeper into lesser-known spinal cord research.

He eventually found something else that excited him. After a skiing accident left a woman paralyzed in 2005—her spinal cord was completely severed—surgeons in the U.S. removed the damaged part and filled the gap with collagen, hoping the ends would fuse together naturally. A year and a half after the surgery, the woman could move her legs again.

Canavero decided this success, which defied medical dogma, demanded more research. “I had been taught spinal cord regeneration is not possible,” he says. “That was the proof that I had to accelerate the whole process.”

The key, Canavero believes, is polyethylene glycol, or PEG, a type of gel that accelerates spinal cord fusion. He thinks that making a clean cut and then applying the gel would allow the spinal cords to fuse, rather than remaining frayed. That fusion would restore the pathway necessary for signals from the brain to reach the rest of the body.

He and other scientists on his team have released several papers that appear to show that his technique could work. In a study published in the Wiley journal CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics, rats regained the ability to walk 28 days after being paralyzed. In Canavero’s mind, once you have the spinal cord problem figured out, the rest of the operation is just a case of connecting tissues.

He decided his plan should at least be given a try, which is why he announced in 2013 that he was going to do the world’s first human head transplant. This did not go down well. The scientific community was outraged—fellow neurologists condemned him as a fame-hungry narcissist who should be put in jail if he performed the operation. One prominent surgeon, Hunt Batjer, from the University of Texas Southwestern, also said that whoever underwent the surgery faced a fate “worse than death.”

In theory, a disembodied head could survive in suspended animation, staying alive with blood from the donor body but incapable of controlling any bodily function—and in incredible pain, says Jerry Silver, a professor of neurosciences at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio who has spent his career seeking a cure for paralysis. The head will have a “miserable existence,” where it won’t be able to breathe or control its own heart rate—a fate far worse than being a quadriplegic. The head’s windpipe would be attached to a respirator, so it could be ventilated, and it could remain alive like that for days.

Scientists also ripped into the work Canavero cites as evidence supporting his approach. One study, by a team of South Korean scientists involved in Canavero’s project, drew considerable criticism for something published in the journal Surgical Neurology International (SNI). They had severed and re-fused the spinal cords of rats. Four of the animals drowned in a laboratory flood after the surgery. But instead of repeating the experiment, they concluded it was a success because the one surviving rat could move a bit.

Scientists also ripped into the work Canavero cites as evidence supporting his approach. One study, by a team of South Korean scientists involved in Canavero’s project, drew considerable criticism for something published in the journal Surgical Neurology International (SNI). They had severed and re-fused the spinal cords of rats. Four of the animals drowned in a laboratory flood after the surgery. But instead of repeating the experiment, they concluded it was a success because the one surviving rat could move a bit.

This was one of a series of studies on head transplants published in SNI—a journal Canavero just happens to be the editor of.

Silver says the studies Canavero uses are not good enough because they used small numbers of animals, often with no control group. Plus, animal models supposedly showing fixed spinal cords do not justify doing the same with people. “You’re not going to jump from rodent to human,” he says, adding that Canavero’s head transplant plan is “criminal.”

And regardless of whether these experiments lend support to Canavero’s theories, they are also disturbing. A rat with the head of another rat sewn onto its back or an unconscious monkey with Halloween-esque neck stitches is outside the bounds of acceptable scientific inquiry and threatens to turn Canavero into a Dr. Frankenstein figure creating monsters under the guise of scientific research.

Karen Rommelfanger, neuroethics program director at Emory University in Georgia, raises one other intriguing caveat: the possibility that this operation is a sanitized version of murder. “If you still have a brain that’s alive...then to take that head off and take the body away, are we possibly killing someone?” she says.

Darren Ó hAilín, a doctoral molecular medicine student in Germany at University Medical Center Freiburg, says human head transplants are a very long way off, and that Canavero and his researchers are offering “disparate pieces of the puzzle and creating the illusion of a cohesive plan.” In reality, all we have as of now are “a mishmash of preliminary experiments.”

Instead of patiently and meticulously building on their findings, says Ó hAilín, Canavero is charging ahead. “He’s going directly to the press with pictures of a monkey’s head stitched into a monkey’s body and saying, ‘Here, we did it.’”

Canavero objects to the notion that past studies have lacked a control, a group of patients who did not receive the experimental treatment, so the results can be compared. He contends that only one of the studies lacked a control group, and that in that case, it wasn’t necessary. He and his team severed the spinal cord of a dog, which subsequently appeared to regain some movement. As a single case study, it provides proof (in Canavero’s eyes) that the spinal cord can be re-fused.

Canavero objects to the notion that past studies have lacked a control, a group of patients who did not receive the experimental treatment, so the results can be compared. He contends that only one of the studies lacked a control group, and that in that case, it wasn’t necessary. He and his team severed the spinal cord of a dog, which subsequently appeared to regain some movement. As a single case study, it provides proof (in Canavero’s eyes) that the spinal cord can be re-fused.

Most popular: Posters of Saudi Crown Prince Are Being Torched in Lebanon Amid Growing Proxy War Between Iran and the Gulf Kingdom

He sees his work as akin to the Wright brothers finally taking to the air for the first time. “It was just one plane, but it was enough to prove flight was possible,” he says. The dog, says Canavero, is like his first plane.

Two Heads Better Than One?

Two Heads Better Than One?

Canavero has at least one kindred spirit: Xiaoping Ren, from Harbin Medical University, in China. He will assist Canavero with the operation in December. Ren has performed thousands of head transplants on mice. The pair connected after Canavero published his human head transplant plan. “It was like falling in love,” Canavero says, describing their first meeting. “Two minds from such a distance that wanted to do the same thing. It was incredible.”

Now, they will have a chance to work together on their shared dream.

Canavero says the people who want this operation are willing to risk everything because they have nothing left to lose—they have no quality of life and are, in all likelihood, dying a slow and painful death. If the transplant fails, then at least they will die knowing that no effort to save them was spared. If it succeeds—well, then they have made medical history. And, of course, are still alive.

Silver objects to the notion that Canavero is giving someone a last chance at life. The memory of a monkey head transplant he witnessed as a postdoctoral student and the knowledge of what the patient could be facing is too much to overcome. “It looked horrifying,” he says of the monkey, “and in pain.” Even if Canavero were able to get some of the nerve and sensory fibers to fuse, says Silver, the pain could be unbearable.

“Every muscle, the bones, everything has been severed,” says Silver. “Can you imagine the pain from all those cut things? That’s the worst. The head is going to wake up in pain.”

Even if Canavero manages to connect the two ends of the spinal cord, the brain will not be able to take control of a new body, Ó hAilín explains. Although it’s true that our brains constantly rewire from the day we are born to the day we die, expecting a brain to adjust its wiring to a whole new body is wishful thinking. “What happens if those wires don’t connect?” says Ó hAilín. Doctors also fear how the body will react to its new brain. In any transplant, the body sees the new organ or limb as foreign tissue, and the immune system attacks it. Patients who have a transplant have to take immunosuppressant drugs for the rest of their lives to prevent this rejection. And if the immune system attacks the new part despite the drugs, it has to be removed.

Even if Canavero manages to connect the two ends of the spinal cord, the brain will not be able to take control of a new body, Ó hAilín explains. Although it’s true that our brains constantly rewire from the day we are born to the day we die, expecting a brain to adjust its wiring to a whole new body is wishful thinking. “What happens if those wires don’t connect?” says Ó hAilín. Doctors also fear how the body will react to its new brain. In any transplant, the body sees the new organ or limb as foreign tissue, and the immune system attacks it. Patients who have a transplant have to take immunosuppressant drugs for the rest of their lives to prevent this rejection. And if the immune system attacks the new part despite the drugs, it has to be removed.

Canavero dismisses this problem, certain that a rejection of the head can be managed in the same way as a kidney or heart. But there is no evidence that immunosuppressants can overcome a body’s reflexive rejection of a new brain.

There is also a potentially staggering psychological impact. The brain may not be able to accept its new body, a phenomenon seen with other transplant surgeries. Clint Hallam, the world’s first hand transplant patient, had it removed after becoming “mentally detached” from it—he could not see it as part of his own body.

There is also a potentially staggering psychological impact. The brain may not be able to accept its new body, a phenomenon seen with other transplant surgeries. Clint Hallam, the world’s first hand transplant patient, had it removed after becoming “mentally detached” from it—he could not see it as part of his own body.

None of this concerns Canavero. He believes that if his patient survives the operation, they can deal with any subsequent issues as they arise. In the 1960s, Christiaan Barnard performed the world’s first heart transplant, doing several things that today would probably be considered unethical—technically speaking, the donors he was removing beating hearts from may not have been dead. Barnard also had to have known some people would die as a result of his operation, but he proceeded anyway, and now, heart transplants are a common—and lifesaving—procedure.

Canavero is aware of the danger and places some responsibility with the patient, who has volunteered. “Let’s not be stupid—this is a risky surgery. But informed consent means that whoever goes under [my knife] knows full well what lies ahead and is in such a crippling condition that there is no other strategy for them.”

He also points out that uncertainty is part of medical advances. Gene editing and immunotherapy techniques currently being developed also come with risks, Canavero points out. One immunotherapy trial had to be put on hold last year following the death of three patients.

Canavero sees his forthcoming operation as a boon for not just people in need of spinal cord surgery but all humanity. Medicine, he says, has failed us. Despite all our best research efforts, we still haven’t got a cure for cancer, HIV, malaria and countless other fatal conditions. Breakthroughs, he believes, will come only by taking risks.

If successful, the operation would provide a treatment option for people with quadriplegia or muscle-wasting diseases that leave them incapable of moving. A body riddled with cancer could be replaced, for example. The most radical possibility is that transplanting heads could lead to a form of immortality—swapping an old body for a new one whenever it’s required, like changing tires on a car.

The many issues relating to Canavero’s plan remain unresolved (to put it mildly), but his team is planning to perform the operation in December. If it succeeds, Canavero will become a giant in the history of medical research.

And if the operation fails, he will try again. He knows that’s the only way to get ahead.

More from Newsweek

Comments