An Indigenous Society Where Women Were Never Housewives

By Okechukwu Okugo

A housewife is regarded as a married woman whose main occupation involves taking care of her family, doing housework, and managing household affairs only, according to a source. Even though, in reality, these tasks are no small job, Igbo women have always historically played more than these roles in African society.

In a typical African society, many had been regarding daughters, wives, sisters, and women in general, as “common housewives,” who are passive in their role and have little or nothing to contribute towards the general economy of the society, but in the Igbo society, the women are actively involved in almost all the facets of economic activities, and are the real brains behind every prosperity experienced in their homes and communities from pre-colonial times.

Igbos live in the southeastern part of the geographical place they named Nigeria, in the western part of Africa. Aboriginally, they largely engaged in three major occupations: trading, crafts, and farming. And women played a leading role in all sectors.

In Igboland, there were occupations exclusively left for the men, for example, blacksmithing, a job that has almost, if not already, become extinct in this age. Also, in cultivation, only men farmed yam while women farmed the cocoyam. Still, in all other areas, women played and continued to play a major role.

Below are some of the ways the Igbo women proved that from indigenous times, they had never been housewives but rather the pillar of their communities’ prosperity:

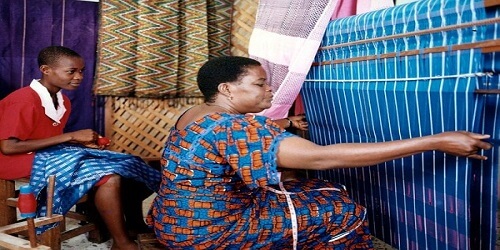

The Igbo Women Clothed The Men, Women, and the Society at large:

Many Igbo societies are known for cloth-weaving with wool, cotton, raffia from palm trees, and other local materials. Places like Nsukka, Akwete, Abakaliki, Aniocha, the Oshimili areas of Igboland, etc. Through their local artistic capabilities, they mass-produced elaborate and colorfully designed cloth by which men, women, and children gorgeously adorned themselves.

Julia Austin, quoting Colleen Kriger’s book, Cloth in West African History, in his article at www.afktravel.com, stated that the famous Akwete cloths appeared in European museums in the 1880s and the 1890s. And give credit for the invention to a woman named Dada Nwakata. Quoting the book on how she clothed both the men and women with her Akwete clothing style, the article elaborated, “There are two types of loom – horizontal for men and vertical for women.”

Giving full credit to women for clothing in Igbo society, it said, “In the early days of cloth weaving, the men of Igboland fished, and the women made the cloth from local materials. For the most part, that’s still the way it’s done today.”

People from all over the world still tour this Igbo community, Akwete, in Abia State to buy different kinds of these hand-woven fabrics, unique from the cloths produced in the entire world. Women who weave Akwete cloth today are never taught how to do it. They simply start doing so at a very young age. That is why people considered this kind of cloth-weaving as inborn talent. It may also be interesting to note that weavers from this village went beyond clothing in their society to producing cloths on an industrial scale in the late nineteenth century, which was why Akwete cloths started penetrating different parts of Europe back then - the power of Igbo women's ingenuity and contribution to humanity.

A colorful Akwete cloth is on display. Photo credit: https://afktravel.com

A colorful Akwete cloth is on display. Photo credit: https://afktravel.com2

Indigenous Igbo women produced industrial and household products:

In olden societies, commodities like salt were valued exactly the way crude oil is valued today. This was because salt serves not only as food but as medicine and a medium of exchange or currency in the Igbo communities and beyond. The book Igbo in the Atlantic World: African Origins and Diasporic Destinations, edited by Toyin Falola and Raphael Chijioke Njoku, noted that “Salt production was associated with women in Igbo Society.” Even though it may have been limited to Igbo communities with brine lakes, areas like Okposi, Uburu, Abakaliki, etc.

Photo credit: Nigeria Galleria

Photo credit: Nigeria Galleria

The productive capabilities of Igbo women were versatile. They also produced black palm kernel oil (Ude Aki), the liquid black gold, because of the many things this ancient African oil performs.

According to www.pharmanewsonline.com, black palm kernel oil is used mostly on children to manage “Epilepsy, cold, and to strengthen the fontanel at 0-12 months old or even more. When a child is constipated, this ‘wonder oil’ is applied to the anal region. It relaxes the muscles and results in easy bowel movement.”

It is also used to treat “children with high fever and convulsion, abdominal pain, as well as skin rashes.”

The efficacy of this oil produced by Igbo women was not limited to children in benefits. For the aesthetic beauty of women, it moisturizes their coarse hair and makes it luxuriant. “It prevents stretch marks” and removes “wrinkles” when generously applied daily on the skin.

The website continued to list the benefits of this oil as an ointment that helps “The healing of wounds and bruises.”

Because of its medicinal value and what it does in manufacturing, this palm kernel oil (Ude Aki) is called "liquid black gold." Photo credit: Pharmanewsonline

Igbo women also used this black palm kernel oil in making soaps, washing powders, hair creams, and other personal care products. With ashes from palm tree leaves, plantain skins, certain tree barks, and oil from palm and coconut, etc., Igbo women produced the famous African black soaps that remove razor bumps, black spots, and eczema and smoothen the skin. They made all these for home use and sold them in the local markets.

In Trade, Igbo Women Control And Dominate The Local or Village Markets:

From primordial times, Igbo women have been known to go to the local market to sell different kinds of locally made articles or farm produce. The same book, Igbo in the Atlantic World: African Origins and Diasporic Destinations, opined, from ancient times, “The Igbo were engaged in local and regional trades. Markets were usually held during the cycle of a four-day week (The days were named Eke, Orie, Afor, and Nkwo). Some markets were held every eight days. These were usually big fairs attended by traders from different Igbo polities and their non-Igbo neighbors. Some village markets were held daily, usually in the evenings.”

It continued, “The maintenance of the village marketplace was the responsibility of women. While more men than women were engaged in long-distance and regional trade, traders at the local village markets were predominantly women.”

Igbo women selling palm oil and other farm produce in a local market. Photo credit: Susty Vibes

This x-rays the typical ancient Igbo market configuration, which is still much the same today in Igbo rural and semi-urban areas. And women continued to play their dominant roles in rural Igbo markets to date. It is also noteworthy that women from riverine areas like Onitsha, Osomari, Aboh, and Oguta, according to the book, took advantage of the network of rivers using water transportation by canoe to “Fairly compete with the men in long-distance trade.” The Igbo women have always known how to utilize opportunities in whatever facet of the economic life of the community it was presented.

In Crafts, Igbo Women Mass Produced Different Utensils Both For Home And Economic Uses:

It is true that crafts like blacksmithing were predominantly men who were producing sophisticated tools for farming, war implements, and artistic and household utensils using copper alloy castings, bronze, etc. But pottery objects were predominantly made by Igbo women. Historic archeological objects discovered at Igbo-Ukwu, in Anambra State, dating back to the tenth century, demonstrated the artistic and scientific capabilities of the ancient Igbo society.

The same book, Igbo in the Atlantic World, confirmed that “Pottery was another local industrial craft associated with women. The Inyi, Nsukka, Ishiagu, Unwana, Isuochi, Okigwe, Udi, and Umuahia achieved regional recognition as pottery specialists. The sizes, designs, and shapes of the earthenware depended on their intended purposes. These included household utensils, musical instruments, and ritual objects.”

Thus, in this way, Igbo women mass-produced these pottery utensils (the ones used in eating were called “Oku” in local parlance. And the clay pot used to play in musical dances, called “Udu.”) both for home use and for the local markets.

5 Agriculture:

Even in Agriculture, though men dominated it in primeval times, women did not play a passive role; rather, they played some active and major roles. The yam was cultivated exclusively by men and provided the staple food for the Igbos, which is also a key measure of a man’s wealth, as men’s status was rated by the sizes of their yam barns and farms; however, cocoyam and cassava considered in Igbo societies as "female crops" were cultivated by the women and they are a subsidiary or an alternative to the yam. Even though most men, especially the titled ones in those days, do not eat cocoyam or cassava because of its perceived “inferiority” to the yam. But in all, it was majorly the crops cultivated by the women that sustained the family daily. Men cultivated only yams, but the women cultivated not only cocoyam and cassava but different kinds of vegetables, peppers, etc., without which no staple meal can be cooked. At the same yam’s cultivation, for which the Igbo men took chieftaincy titles after, like Ezeji, etc., the men wouldn’t have been successful without the help of the women and their grown children who lend them a helping hand while they cultivated the yam.

Farm labor is chiefly provided by the members of the household. So, the men counted on the help of the women and their children in tilling the soil, clearing the farmland, planting the seeds, weeding and maintaining the farms, and harvesting and transporting home the farm produce. Generally, in the end, the Igbo women spent more time at the farms than the men, considering all the other tasks they perform on the farm before and after the cultivation of the crops.

The book quoted at the onset also showed that the efforts of Igbo women go beyond the farms, stating, “Food processing and preparation were solely the responsibilities of Igbo women with their children’s assistance.”

Thus, Igbo women function more than as wives in Igbo homes. They act as a family doctor. They are more than the family chefs, acting as the family sustainers, considering their roles in food processing at home. Thus, the activities of Igbo women naturally and unavoidably enlarged a man’s economy, playing a major role in bringing cash into the home. The reason why single Igbo men had always been poorer than family men in those ancient communities; it does not matter how massive the strength such a single man possesses; a family man with a naturally industrious Igbo wife would always do better economically because of the extra hands and the ingenuity provided by the wife.

Igbo women farming rice in Abia State. Photo credit: Igbo News

It is inarguable that the income of men with larger families in those days surpasses that of single men. The secrets of the financial successes of the Igbo men and the Igbo society were that at no time had the Igbo men relegated their women solely to the kitchen or only confined them to the chambers of child-bearing and rearing. Rather, the natural Igbo society had allowed their women to utilize every opportunity in their homes to exhibit their capabilities and talents to the economic upliftment of their homes and the Igbo society at large.

That is why, from time immemorial till date, Igbos have always been proud of their hardworking mothers.

Opening photo credit: Google Sites. This post was updated on 11/30/2022.

Akwete cloth weavers at work. Photo credit:

Akwete cloth weavers at work. Photo credit:

Comments